א ויהי כל-הארץ, שפה אחת, ודברים, אחדים

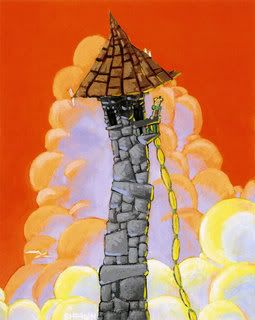

ד ויאמרו הבה נבנה-לנו עיר, ומגדל וראשו בשמיים, ונעשה-לנו, שם: פן-נפוץ, על-פני כל-הארץ

Why is this story even necessary? If we removed it from the Torah, we might not miss it at all. In fact, it seems, much like the non-ending genealogies of hard to pronounce names, and wholly redundant. Yet, for the purpose of which the story becomes necessary, it fits right in with the aforementioned family trees. The tale of the Tower is not needed, in and of itself, but exists to fill in a ‘blank’. While reading thus far in the Torah, one wonders how multiple languages, human migration, and demographic diversity came to be. In the mind of the ordinary person, families stay close to families and, in those days, people stayed near the clan and rarely ventured very far from home. To anyone alive then, the idea of migrating away from your people was considered insane, so the Torah has to tell us that God 'forced' people to do the unthinkable and spread out far and wide across the globe. As we see with Cain, having to leave the family was a terrible curse!

Verse 11:1 tells us what humanity looked like immediately prior to the Tower and, at the same time, leads us to some more interesting questions. So far, despite the racial differences we are told existed between Noah’s children, they seemed to be, at least we imagine them to be, of one huge and very cooperative extended family, while speaking one common language among each other. There is no reason to assume otherwise and it makes perfect sense, should the Torah be correct, that one common means of verbal communication among these cousins was the norm. That everyone shares a bloodline, lives within the same community, and speaks a common language should come as no surprise. After all, they were grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the same man.

However, if we take allow ourselves a moment of respite from our Torah reading to take a quick glance at the world around us, we see something very confusing. Whether in ancient or modern times the various traders, merchants, mercenaries, ministers, refugees, and vacationers from distant lands, none of whom spoke the local language, began arriving within the boundaries of the fledgling human family. The clever child would immediately ask the obvious question, and the Torah anticipates that curiosity with the Tower story. It became necessary to explain to children (and I suppose some adults, too) how such varied linguistic diversity came to be if, in fact, the Torah, up to that juncture immediately prior to the Tower, was even remotely accurate. Thus, the telling of the tale of the Tower of Babel was needed to answer the obvious and keep the flow of the Torah narrative running smoothly.

Why did they build the Tower anyhow? The Torah says that the people were worried that they would become too spread out and wanted to establish the Tower as a beacon which people could see for many miles around, much like a lighthouse does for ships nearing the shoreline. There is nothing here to substantiate the Rabbis claims that these people were going to 'make war on God' and eventually climb the Tower to attack Heaven. I realize the Rabbis have to concoct that nonsense to try and make sense of the story, which is also nonsense, but they just make the whole problem even worse. From the plain Torah account, there appears nothing amiss or sinful in their motives for building a metropolis or a skyscraper within it. One has to wonder how, in light of the Tower story, this God allowed any cities to ever be established.

The Rabbis reasons for assuming a 'war on heaven' are two-fold. One, it provides a reason why God would be angry over this and two, it permits all kinds of other assumptions clearly not stated in Torah. We will deal here with only the first assertion. The obvious question becomes as to how exactly one wages war on an Omnipotent, Omniscient, Omnipresent being. It's not as if one could launch a direct assault on something which is everywhere nor could one ever hope to hold the high ground or use the element of surprise to any particular advantage. Besides, what weapons would they have been using? If God is vulnerable to spears and swords, whereas God being equally present everywhere one turns, He would have to fear the blade at sea level just as He might at 5000 km above it!

Why build the Tower in the valley and not on a mountain top? If their purpose was, as the Rabbis suggested, to ‘wage war with God’, then wouldn’t it make more sense in any case to use existing geography to their tactical and practical advantage? I think it's pretty clear that the Rabbis were talking out of their asses, merely trying to justify the Tower story through the smoke and mirrors of allegory or parable, rather than dissecting the Torah account to root out the apparent flaws.

Rabbis say that humanity's sin here was in developing too much self-reliance and not maintaining enough faith in God. The 'war on God' was not a literal war in the physical sense, but a psychological war whose indirect effect would be to lessen one's dependency on God. The Rabbis assert that the people, by establishing themselves as a civilization, were rejecting faith. Apparently, only nomads and farmers are steadfast in faith and belief and God was worried that living in anything other than tents that reek of dried camel dung and human urine would incite humanity to rebel against Him. If real faith can only exist in nomadic agrarian societies, then modern Judaism is utterly screwed. In either case, the Tower tale makes no sense at all.

Who is God asking to help confuse languages? When He decides that "We" should be doing something about the Tower, who is asking? This is a similar problem to the verse in genesis where God says "Let US make man". So who is us? Now you may suggest that 'us' here is perhaps angels, but why doesn't it just say 'angels' and not leave us guessing? I have no answer for this one, and it appears to be yet another instance where polytheism is strongly implied in the Torah. This problem, however, is not integral to our story.

What is God's problem with peaceful human cooperation? It seemed that humanity was doing quite well; without wars or other societal problems that, under the best of circumstances, tend to fragment a society. This is, in part, how you know the story to be false. I cannot, myself, imagine all of humanity, no matter how few in number, working toward one purpose so efficiently as to scare the bejeezus out of the Almighty. One has to ask what exactly it was about their peaceful and focused mutual effort that ticked off the Lord. Not only that, but you’d think that all this happy cooperation would be a really good thing and not pose a threat to God. After all, just a few generations back, God flooded the planet and damn near wiped out humanity for NOT behaving peaceably with each other! So now, they are conducting themselves quite nicely and God gets pissed off at that, too! No wonder people stop believing in God; he is just plain impossible to please!

How exactly did God mess up their communication and to what extent? Rashi tells us that if one worker would ask for a brick the other would hand him a hammer and this thwarted any effort to continue building the tower. Yet, to have total societal confusion spring from this incident, it would require much more than just the mere bewilderment of artisans and laborers. For God's plan here to unfold as desired, both husband and wife, parent and child, brother and sister, etc. would also have to become linguistically estranged from one another. The result would be that no one, even those on the most intimate of terms, would be able to communicate! Total chaos, and one well beyond what the Torah suggests here, would have almost instantaneously ensued. Yet, somehow, the people did not disperse as individuals in random chaos, but remained, even while migrating away from Shinar, in their basic family units.

This problem is further accentuated by the fact that, as the Torah claims, they were of "few words", implying a language very much based upon symbols, signs, and other forms of non-verbal communication. If we are to believe what Rashi tells us, then even if their spoken language went awry, the basics of their communicative abilities still remained. This applies even more so to the artisans and laborers whose skills, once highly developed, required no direction at all, as they were able to continue their work without need for spoken language. If a mason needed a brick he could simply point with his finger to the brick and the laborer would know what to do. In any case, whatever the Torah (or Rashi) claims to have happened either would have had a much greater or significantly lesser effect than the Tower story seems to imply and does not answer any of the obvious questions.

The list goes on, but I have no more time at the present to donate to this subject. Comments and ideas are always welcome.

Kol Tuv